Product marketing leverages the desires of people.

For many in IT getting rid of the complex ETL development, operations, and maintenance is one of these desires . Sometimes the business people shares this desire: to finally get free from the need to explain to non-business people (and sometimes challenge their own belief about) how the business works.

The data lakes in their original incarnation (in practices data swamps) promised to achieve this but didn’t live up to the promises.

There is also another solution, that didn’t suffer the same bad press, that promises to free the IT team from the need to have “complex ETL”: data virtualization/data federation.

In this post I’ll try to dispel two myths about data federation.

Myth 1: Data Federation removes the need to design complex ETL

ETL usually is not complex because of the tools used or a lack of skills.

The purpose of ongoing ETL is to extract new data from a number of source systems, manipulate it (clean, conform, track historical changes for slow changing dimensions, make hierarchies easier to use…) and produce new datasets that are useful for the business (i.e. data that enables the organization to make better and/or faster business decisions that will increase its profits).

The intrinsic complexity of the manipulation that needs to be implemented in the ETL is derived from the business processes: no tool will ever remove this complexity.

Intrinsic complexity can only be moved around, but never removed.

When a virtualization tool promises to “remove the complex ETL” what is really saying is “someone outside the ETL team will have to manage this complexity”: at best it is shifting the effort from one team to another within the organization. For example from the IT team to the business people. Or from the ETL team to the BI team within IT.

This is pretty much the same sleight of hand that was attempted with many of the early data lakes: store the data without much/any transformation.

The net result of many of the attempts was that the business users couldn’t utilize the data in these lakes in an efficient way. If at all.

Myth 2: Data Federation removes the effort needed to “run” the ETL

This is very true in the literal sense, but it is also very partial.

Replacing the ETL with a federation solution makes much harder to troubleshoot problems because intermediate datasets are not saved and available for review.

Because the data in the source systems is changing continuously it’s almost impossible to reproduce exactly the results the users complained about.

Ensuring in the federation approach a level of data quality comparable with what is achieved with the ETL can be cost prohibitive and the queries so slow that the user experience is unacceptable.

Extracting data from the source system during regular working hours adds load to the operational systems and also to the teams managing them.

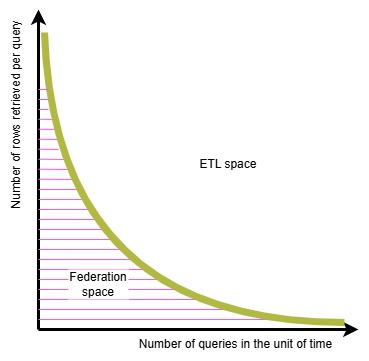

If the number of queries executed for the the specific use case is small, the data moved is modest, and there is not expectation of a significant growth in either dimension, you are safely in the “federation space“. If this is not the case then you must properly benchmark your solution and avoid a “kick the tire” test.

Conclusion

What you can get easily with a data federation solution is different from what you can get easily with an ETL solution.

Pretending this is not the case suggests a gap of knowledge and real-world experience.

The best solution is the one that addresses your organization’s (i.e. including the users’) needs with the most acceptable set of trade-off today and tomorrow.

P.S. In any case never challenge an experienced supporter of one of the two approaches: you can rest assured the person will find a very intricate, and costly, way to prove his tool of choice can do everything you say it can’t.

This is the reason why is purposely added the “easily” adverb in my conclusion.