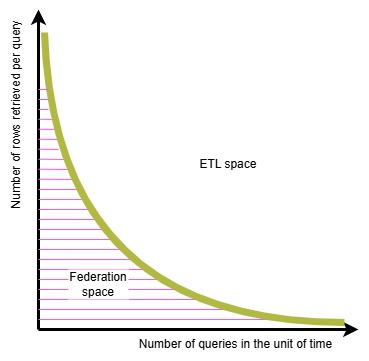

I recently posted about the “federation space” and how there is a sweet spot for the use of data virtualization / data virtualization solutions to perform data analytics.

In the post I promised to discuss two optimization techniques that promise to extend the viability of running queries on distributed data.

Query push down

To anchor the discussion I’ll use a pseudo-code query.

The simplest query on distributed data can be sketched like this:Select some_calculation from remote_table

For my example I’ll take “some-calculation” to be the average of the value of “column_a” in the remote table containing, let’s say, 10 rows with 10 columns per row.

– The most trivial implementation will perform the sample query by fetching the entire remote_table locally (100 values retrieved) then calculate the average.

– A slightly smarter implementation will push to the remote system the request to send across only the values of column a (10 values retrieved)

– A good, modern implementation will push the entire query to the remote system and retrieve only the desired average (1 value transferred across)

It all looks great in the simple example, but the reality of analytical queries is seldom this trivial.

A slightly more realistic pseudo query might look like the following:Select customer from remote_spending_table, local_customers_segments_table where customer_spending>2[*average(all_foreign_customers_spending)] and customer_segment="foreign")

The purpose is to retrieve the list of foreign customers that are spending more than twice the average spending of the foreign customers

This generates two challenges:

1) correctly identify the extent of the possible query push down and translate it to the remote system’s SQL dialect (is already not trivial for this small example, just imagine with the 3000-lines-of-SQL generated by the MicroStrategy report of one of my German customers in 2010)

2) getting the owner of the remote system to agree on consuming its resources to execute our query.

Running a simple filter is much lighter than running an aggregation and it’s easier to get an agreement to it.

The second challenge is partly mitigated if the source in the cloud

Thanks to the cloud elasticity the negative impact in the source system can be made negligible or non-existent.

But the topic of who’s paying for the computing costs remains in place (unless it’s a single entity that pays for all the infrastructure costs).

Caching

As soon as a data virtualization project gets adopted the increased load on non-elastic on-premises source systems becomes unacceptable (because the original workload performance is negatively impacted) and the users of the analytics queries start to experience longer response times (because the source system is overwhelmed).

The solution to this challenge is to introduce a caching layer that will store a copy of (part of) the data near the data virtualization system. If properly sized the cache improves the user experience both for the source system’s users and for the people running the analytical queries.

The caching layer also helps reducing the egress costs when consuming data in a hybrid cloud setup. Microsoft’s Blog post about the introduction of S3 caching to OneLake just confirms it.

The first victim of caching is the vision of having “no data duplication (thanks to data virtualization)”, but it is not the only one.